Reflections in the Modern Mirror

On the Roots of American Narcissism

THE KOINOS PROJECT is an online educational platform restoring humanity to the Humanities: a place for the intellectually curious, but educatedly stunted searching for something more—for a true mythos. Subscribe now to stay up to date on all our offerings.

A FEW MONTHS AGO, an article was published in a mainstream magazine about a celebrity who frequently stares at herself in the mirror while masturbating. This practice, she says, helps her work through her body-image problems. I hope it works and that she finds what she is looking for.

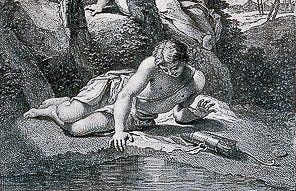

That should be that—I care precious little about what anyone does in the privacy of their own bathroom, looking at their own mirror. Still, the image calls out to be analogized. For we now live in a culture that does a fair bit of staring in the mirror, seeking happiness not in the loving touch of another, or the spirit of community, or the transcendence of religion, but through self-validation.

And yet, for all the ink spilled these days debating the validity of such acts, this is hardly a recent phenomenon. Nearly fifty years ago, the social critic Christopher Lasch noted as much in his book The Culture of Narcissism. Through a nuanced blend of Marx, Freud, and Jeffersonian populism, he offers up an unparalleled analysis of modern inwardness and its many causes:

Americans have retreated to purely personal preoccupations. Having no hope of improving their lives in any of the ways that matter, people have convinced themselves that what matters is psychic self-improvement: getting in touch with their feelings, eating health food, taking lessons in ballet or belly-dancing, immersing themselves in the wisdom of the East, jogging, learning how to “relate,” overcoming the “fear of pleasure.” Harmless in themselves, these pursuits, elevated to a program and wrapped in the rhetoric of authenticity and awareness, signify a retreat from politics and a repudiation of the recent past.1

It’s almost like Lasch wrote these words while reading the article that inspired this piece. But it is not just celebrities. Many of us are “doing the work” and “practicing radical self-love.” All of us try to “find ourselves” and “live authentically,” believing that going ever deeper into ourselves will magically fix the world outside.

AT FIRST BLUSH, Lasch’s words read a bit like your crabby Boomer uncle on Thanksgiving: the kids have gone rotten through self-absorption; the smartphones have taken over; our identity conscious culture fixates on self-discovery at the expense of old fashioned human connection and respecting your elders. If only we stopped thinking about ourselves so much, then all would be well — Narcissism as cause of society’s woes.

But this grossly misrepresents Lasch’s position. Yes, we’re narcissists, he thought, but not because we are morally corrupt. Our overactive self-regard instead is a result of deeper, structural features of modern life in the West. And your Boomer uncle, of course, forgets that it was precisely his generation about whom critics like Lasch were writing. No, narcissism, Lasch argues, is American through and through, something latent in the very core of who we are as a people that can overtake us in the absence of countervailing forces.

This aspect of the American character is nowhere more evident than in the economic realm, an order that thrives on and demands above all else flexibility: innovative products constantly flood the market; companies seek “agility” and expansion; they move overseas or go out of business; people get fired, change jobs, change careers, move up the ladder. As Lasch would later note in his posthumous The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, “Success has never [before] been so closely associated with mobility,”2 and this instability makes enduring relationships challenging. To succeed in business, it would seem, requires shallow roots. And it was only a matter of time, he argues, before this ethos migrated from the world of work to our relationships. What do family and friends, neighbors or fellow citizens matter to “global citizens” at home anywhere?

THE ECONOMIC MINDSET no longer stops outside the front door, but has become soul-shaping. People accustomed to change do so when opportunities present themselves and the character formed by work spills over into the domain of the personal. “The passion to get ahead,” Lasch observes, “has begun to imply the right to make a fresh start whenever earlier commitments become unduly burdensome.”3 Formerly binding relationships of “till death do us part” are now tenuous, subject to endless revision and looking around the next corner for the new and better.

How can we rely on people who always have one foot out the door? What if they get a better job offer in a new city? What if they get a good deal on a new house across town? What if we slowly drift apart as we age, changing as much as the world around us? Hollow out confidence in other people and all you are left with is the self. So we retreat.

Disconnected from each other, we also become cut off from past and future. In a world of permanent revolution, the past has lost intelligibility and relevance. It is not simply Boomers’ memory that is fading, but the entire social structure they were formed by; the lives of our grandparents and even more remote generations now seem like tales from another planet. Whereas the old and wise once educated children, it is now the young and clever who update the old on how the world works. These generation gaps inhibit understanding across time so that only the present makes sense to us.

Indeed, masturbating in the mirror is a perfect image to sum up our collective response to this crisis of belonging and understanding. Therapeutic self-improvement, narcissism, and self-absorption are simply the outcome of a world in constant flux, a world in which it has become increasingly difficult to rely on others. But as tempting as it is to blame this all on individuals’ lack of private virtue, we must also look critically at the economic and political system that so minutely structure our lives today.

“Religion,” Marx famously said, “is the opium of the people, the sigh of the oppressed creature.”4 Narcissism, Lasch might say, is the last retreat of the ever-harried, the sigh of the lonely creature.

The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations, 1979, pg. 13

The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, 1996, pg. 5

ibid. Pg. 95-96

The Marx-Engels Reader, 1978, pg. 54