Some Inaugural Thoughts on the Nature of Difference

Reflections on the future of American Community

THE KOINOS PROJECT is an online educational platform building community through studying community: a place for the intellectually curious, but educatedly stunted searching for something more—for a true mythos. Subscribe now to stay up to date on all our offerings.

WE TALK A LOT about trying to “understand” differences these days. By exposing ourselves to differing ways of life—different lifestyles and perspectives—we believe that we will come to understand the world and ourselves better. But when you look at the actual actions taken in service of this goal, it seems to me to be the wrong verb. The result is less understanding than tolerance, at best, acceptance. We seek to make difference comfortable—both for the different, but above all, for ourselves.

Upon this day in American history, many find themselves faced with the necessity of accepting something different that makes them profoundly uncomfortable. History has not gone according to plan, and now we must learn to live with the consequences. Whether one judges this to be a positive or negative development is not the question here. How we are to now live together is. Tolerance and acceptance (of fate) is certainly one option—it managed to somehow get us through the first time. Or we could use this as an opportunity to live up to our ideals and learn to actually understand what living in a world of difference demands.

Ultimately, coming to understand things other than what we are or know entails exploring the contrasts: comparing it to our own way of life and assaying its values, and thus its value. What our current practice of tolerance does is ignore differences in the hopes of bringing those on the outside into the fold—of making the pariah into a neighbor. These actions, however, are hindrances, not aids, to understanding. In so doing, we unwittingly shut off our faculty of judgement in order not to judge a thing by our standards. But is not judgment the very mechanism through which understanding occurs?

Now don’t get me wrong, acceptance is certainly a necessary first step—if we are too prejudiced, we will never become judicious. By being too quick to judge something, we are liable to place it in a predetermined category that obscures vision just as badly. But whereas prejudice is a wall that prevents approach, unreflective acceptance is an overpass that keeps us equally distant. Both are barriers that prevent getting close enough to appreciate who or what we seek to know.

But now that we have been awoken from the dogmatic slumber of the last thirty or so odd years, how are we to move forward as a nation? How are we to understand this new paradigm, and how are we to understand those miscreants who interrupted our self-satisfied somnambulance? Must we resign ourselves to simply tolerating the next four years as another waking nightmare?

I believe that if we instead make an earnest attempt to understand those who differ from us, it can be a teaching moment by which things we have too long suppressed and ignored may be brought to light. Difference is a good thing; acceptance, equally as good. And in a society as large and diverse as ours, tolerance is paramount. Yet in our rage to make difference comfortable, we have forgotten how to think properly about the consequences of our decisions and what they mean for the lives we wish to lead. Understanding why others believe what they do can be equally revealing about the nature of our own most deeply held convictions. Alternatively, we can say, “Hell with it, may the best team win.” Historically, though, this has never turned out well for anyone involved.

ONE OF THE MOST instructive sources from which I have come to understand the nature of difference is by comparing the ancient Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta. These two societies are a complete study in contrasts, and could almost be said to represent our two fundamental human alternatives in their purest forms.

Modern social scientists would describe Athens as an “open society” par excellence, whereas Sparta embodied the “closed society.” Athens was a sea power: democratic and individualistic with open borders, they engaged in trade and exchange of ideas with foreign lands, and allowed art and philosophy to flourish in its midst. Sparta, conversely, was a land power: oligarchic and collectivist with closed borders, they prohibited all foreign trade and influence, and concentrated their entire society around military virtue. Despite these vast differences, however, at the height of their power in the 5th century BC, they equaled and rivaled one another for supremacy of the Hellenic world, engaging in one of the largest wars up until that time. I believe that by holding these two deeply antagonistic societies up against one another, the true consequences of difference are exposed—of what is gained and what is lost in making choices for oneself and one’s society.

Basically everything we mean when we refer to “Ancient Greece” today (the art and architecture, the philosophy and, of course, democracy) happened in only an eighty year period, in a single city of 40,000 free men. This situation was anticipated, in fact, by one of our greatest resources for knowledge of these two societies, the historian Thucydides. As he observes at the outset of his on-the-ground account of the war that would bring this golden age to an end:

Suppose the city of Sparta were wiped out and all that was left were its shrines and the foundations of its buildings, I think that years later future generations would find it hard to believe that its power matched up to its reputation. . . . On the other hand, if the Athenians were to suffer the same fate, they would be thought twice as powerful as they actually are are just on the evidence of what one can see.1 (1.10)

Yet despite this disparity, 2500 years later both cities continue to ignite the popular imagination, confirming that other famous forecast made by Thucydides: that his work would become a “possession for all time.” As long as “the human condition remains what it is,” (1.22) he contends, his document will continue to shine light upon the dark contours of existence to help illuminate our path.

As the Greek proverb contends, “the beginning is half of the whole,” thus the dialectical nature of these two cities can be seen from their very origins. Whereas the Spartan legislator Lycurgus enacted his vision by force; Athens’ lawgiver Solon did it through persuasion. Whereas Sparta’s laws were divine revelation; Athens’ were epic verse. While Lycurgus fashioned an individual out of a community; Solon made a community out of individuals. As Plutarch, our second greatest source of information about these cities, frames it: Solon merely re-formed Athens to give it “the best laws they would accept,”2 while Lycurgus revolutionized Sparta and instituted “the best laws in the world.”3 And the fact that the latter’s work went practically unchanged for nearly five hundred years (only giving out because of Athens’ imperial ambitions), only reinforces this judgement.

Sparta maintained its continuity through a harsh educational regime that married personal excellence with unquestioning obedience, habitually reinforced by a lifelong regimen of military training. Because Lycurgus forbade his laws from being committed to writing, they needed to be written, and continually retraced, on the heart of each and every citizen. To this end, there was a complete erasure of the family unit, private property, luxury, money, privacy and autonomy. As Plutarch summarizes, “The citizens lost both the will and the ability to live as individuals,” becoming simply “organic parts of the life of the community.”4 Other than in wartime, or when a general was sent out to aid another city, citizens were not permitted to travel abroad, nor were foreigners welcomed into theirs. For novel ideas, bring novel choices, which disrupt the harmony of the whole. Yet just because no one was able to live as they pleased, it did not in turn mean that everyone was equally nothing. Life in Sparta was a continuous struggle for dominance and personal recognition—it was just that they only wanted to see and be seen for the sake of Sparta, not for themselves. Ambition was constantly encouraged and rewarded at every moment of every day, but the only available outlet was in service to the whole.

Athens, by contrast, took a much more laissez-faire approach in enculturating its citizens. As Thucydides describes, the Athenians were “natural innovators . . . bold beyond their means.” (1.70) Their proximity to the sea brought opportunity both for expansion, as well as for incorporation. Athens thrived as the crossroads of the Aegean where ideas met the material to move from ideality to reality. A “spirit of freedom,” (2.35) he elaborates, permeated their society that allowed citizens to live as they pleased—as long, that is, as their choices did not break any laws or undermine the public good. Constant change was not only welcomed but embraced, and the names that have echoed down through the ages—Pericles and Alcibiades, Sophocles and Aristophanes, Socrates and Plato, the Parthenon and the Agora, to name but a few—attest to the city’s liberality and enlightenment. These luminaries, however, also represent the final Athenian epoch to be so commemorated. In their contest for supremacy of the civilized world, Sparta was ultimately to defeat them, and no one was ever able to make Athens quite so great again. While you can still admire the city’s ancient shrines and buildings even today, one is visiting only ruins.

SO AS WE BRACE ourselves for the possible drastic changes to our way of life that many of our fellow citizens voted for, what can we learn from these ancient images?

When we in the modern West say that we “value difference,” or that “diversity is important to us,” we mean this is in an entirely Athenian way: everyone should be legislator of their very own lifestyle. A Spartan existence of austere submission to authority is practically unthinkable—and certainly undesirable—to the majority of us. Difference means individual innovation; and even when we are talking about a company or brand that is “innovative” (which by definition involves some sort of collective enterprise), it means breaking free of the traditional way of doing things. Yet despite the greater individuality granted by Solonic law, there were still particular qualities that made a citizen of Athens an Athenian; likewise, despite its guardedness, a Spartan was given vast leeway to differentiate themselves from their comrades. The ancient conception of both individuality and community seems to have been much broader than how we envision them today.

Indeed, this is the inherent logic of modernity: to move away from a collective identity given by tradition towards autonomy (from the Greek auto-nomos: “self-law”). The last thirty years of radical politics perfectly reveals this fact, as we have witnessed the quiet substitution of the term “multiculturalism” for “diversity.” Equal cultural representation once dominated the leading edge of progressive politics. But once other cultures were sufficiently brought into the fold and these pariahs became neighbors, the push has again returned to acceptance of everyone as a unique individual. But apparently people can only be pushed so far.

Sparta has once again defeated Athens. Upon issues of border, culture, economy, community, and harmony, the Lycurgian desire for unity has reasserted itself against Solonic openness. But the question remains as to what makes those who live in America American? Is it simply shared interests, or a shared set of ideals; or perhaps a shared history and a shared future? More likely the monocultural vision of Pax Americana inaugurated in the 1990s shall go the same way as the “multiculturalism” of that era. So what constitutes the positive vision that underlies the negative vote given to our former historical trajectory?

Today is not a period, but a question mark—at worst an ellipsis. How we fill in the blank is now to up each of us as an individual to decide. America shall always be Athenian to the core, but that does not mean we cannot learn from the Spartan. This is the true value of openness. To me at least, it seems that the latent message underlying these surprising events is a desire for the reconstitution of some sort of real community. But in a world of expanding digital connectedness, and increased mobility and crosscultural exchange, what does such a thing look like?

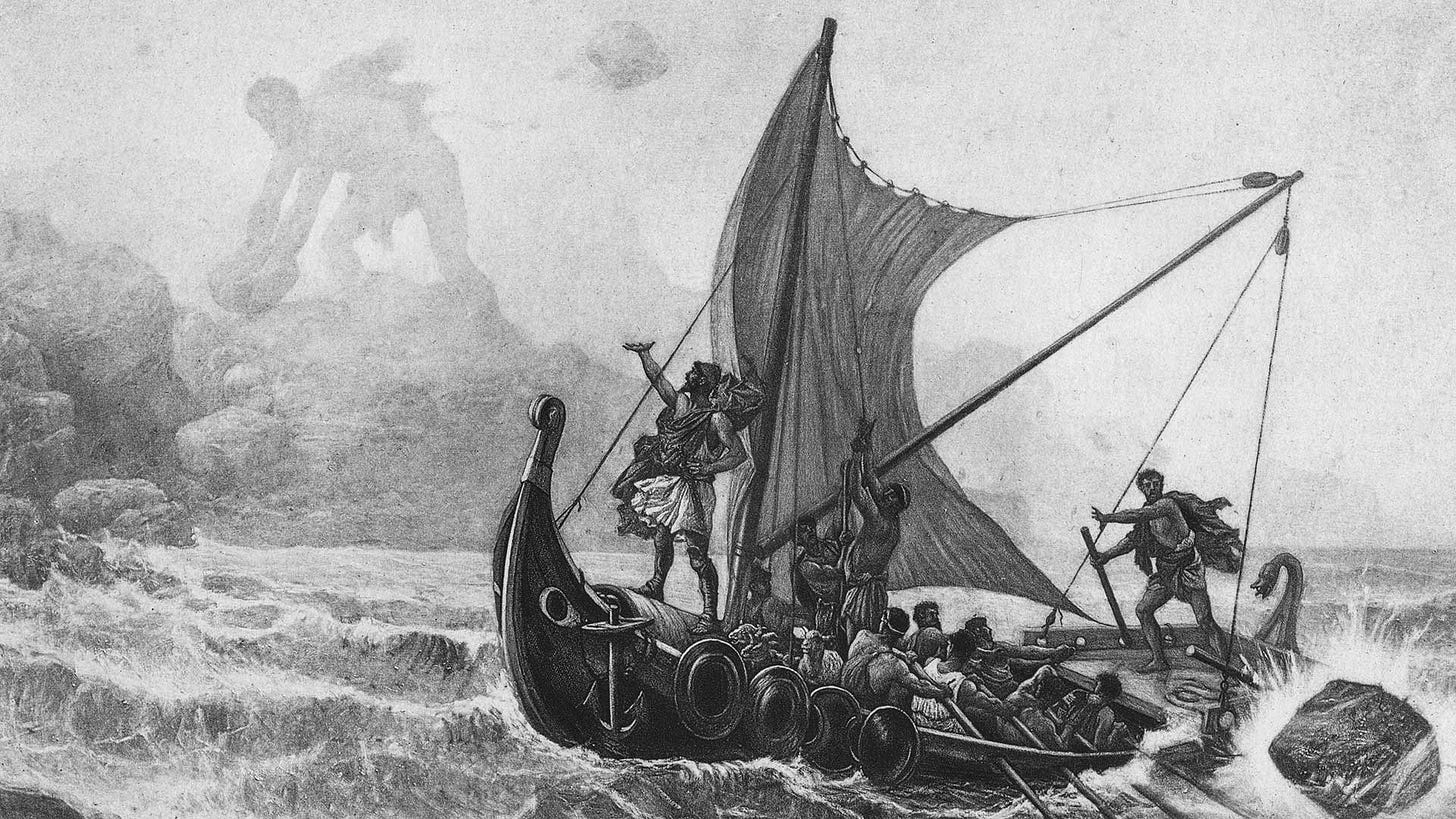

What this election may have ultimately revealed is the limits of the possible. History has not ended; it possibly has not even begun. Only through a better understanding of ourselves and the nature of the human condition that studies such as Thucydides illuminate may we begin to answer such questions. Building community now requires that we study community. Never before in human history have we possessed such autonomy. Join us here at The Koinos as we begin this most exciting of all human odysseys.

Thucydides (2013). The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians (J. Mynott, Trans.) Cambridge Texts in the history of Political Thought

Plutarch (2008). Greek Lives (R. Waterfield, Trans.) Oxford World Classics, p. 59

ibid, p. 13

ibid, p. 39